When AI-written applications meet automated screening

Candidates use AI. Companies rely on automated screening. The result: signal dilution and missed talent. How to design hiring systems that still work when AI is everywhere.

It started the same way every time.

"We have decided not to proceed with your application".

I have a PhD in particle physics and spent over a decade at CERN, including several years of leading international research teams. I could not get past the first round of automated job screening.

The rejection emails were polite and identical. Several colleagues with impressive backgrounds ran into the same invisible barrier. That raised a question: What exactly happens at the first stage of hiring today and what kind of signal does it actually detect?

The current state of automated screening

Most large organizations rely on automated systems to manage the initial round of applications. These systems scan résumés for job titles, skills, and certifications, ranking candidates based on keyword matches.

The efficiency is undeniable, but so are the limitations.

A "Software Engineer" may pass while a "DevOps Engineer" is rejected, even when the skills overlap. Leadership experience can disappear if it is phrased differently from the expected template. Two people can describe the same role in different ways, but software rarely sees beyond the wording.

Somewhere in those systems, a decade of analytical work was reduced to a mismatch between "particle physics" and "data consulting". Different words. Case closed.

When I eventually joined Argusa, I asked my manager what made my application stand out.

She smiled and said, "I review all the applications manually".

That single sentence changed my perspective.

Manual review works in small companies. But once hundreds of applications arrive every week, it becomes unrealistic. The question is no longer whether to automate, but how to do so without losing signal.

The other side: candidates adapt

Another force reshaping hiring today sits on the candidate side.

AI tools help candidates draft CVs, tailor cover letters, and answer application questions - often across many applications. In practice, applicants apply broadly because that is what the current market demands.

Recruiters increasingly encounter near-identical phrasing, generic motivation statements, and occasional copy-paste artifacts like "Would you like me to continue?".

The result is signal dilution.

When everyone can produce polished, competent-sounding text instantly, traditional signals such as motivation, communication skill, even attention to detail lose their differentiating power. The challenge is no longer filtering for quality writing, but for authentic signal beneath the polish.

Hiring systems were designed for a world where polish correlated with effort and intent. That world no longer exists.

A prototype: combining perspectives instead of choosing one

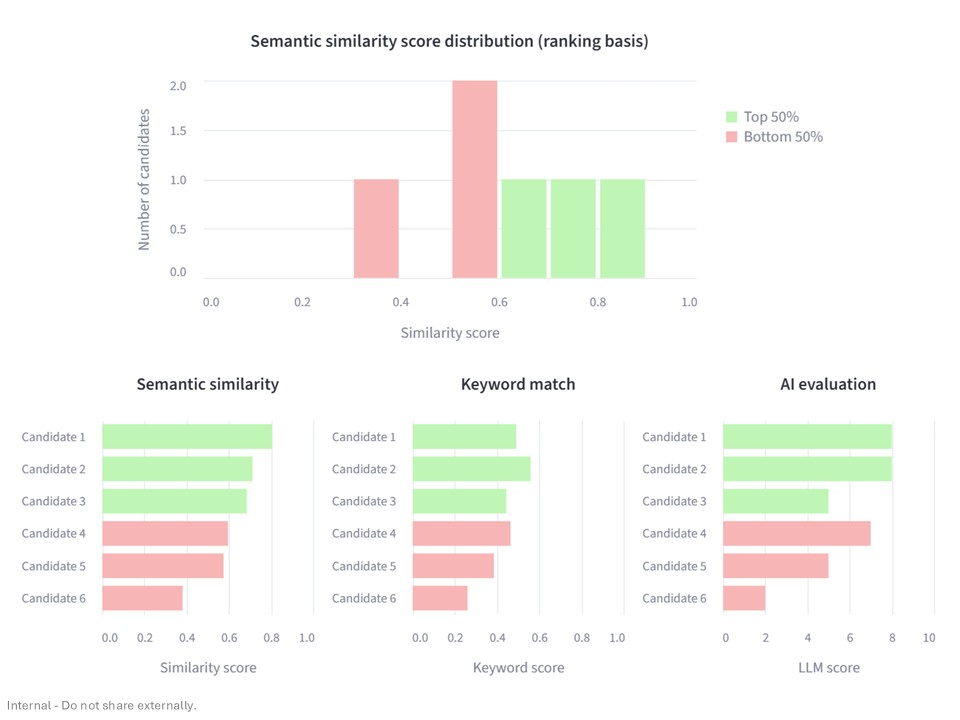

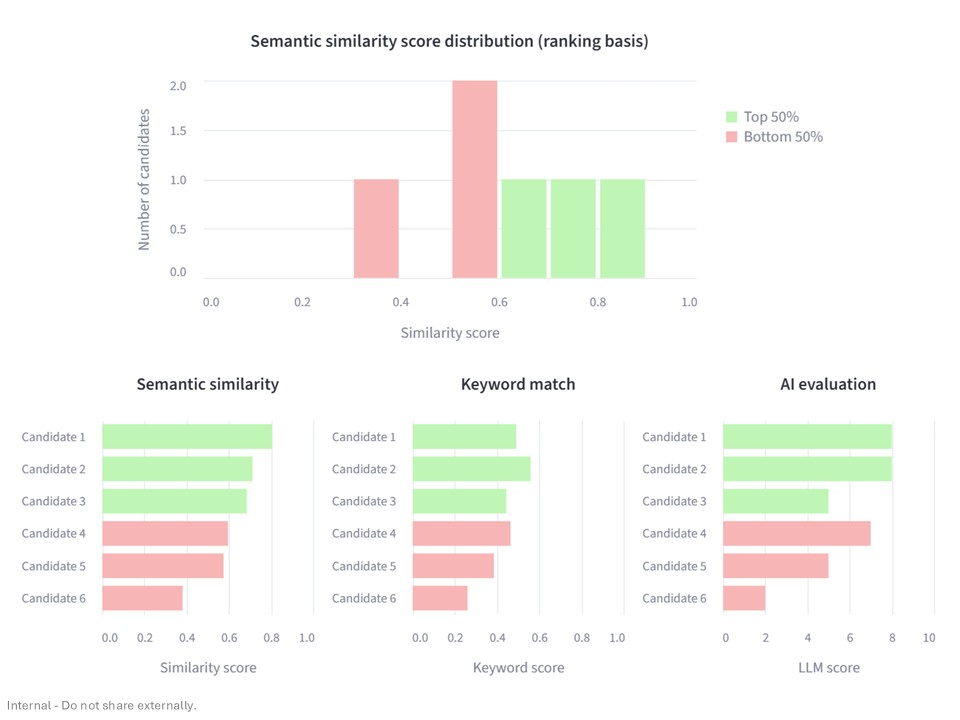

As part of recent work on internal systems at Argusa, I built a small proof of concept to explore an alternative design principle: instead of collapsing candidates into a single score, could multiple interpretable perspectives surface profiles that single-method screening often overlooks?

This prototype was exploratory and was never used in real hiring. It compared fictional candidate CVs to profiles of strong hires using three complementary approaches:

- Semantic similarity: Measures how closely each CV resembles those of our best hires in structure, focus, and language.

- Keyword match: A traditional checklist against required skills.

- AI evaluation (LLM-based review): A written assessment summarizing how a candidate’s background aligns with the role.

Showing multiple scores mirrors how hiring works in practice: we involve multiple interviewers precisely because no single perspective captures the full picture.

However, this approach also has an important limitation: comparing candidates to past “strong hires” can reinforce existing bias if used blindly. This is why these perspectives are intended to inform human review rather than replace it.

Note on data and confidentiality: All CVs used by this prototype were fictional and AI-generated; no real Argusa candidate data was used.

The prototype was designed with anonymization built in, so that even with real candidate data, LLM-based evaluation would operate only on redacted, non-identifying information, while keyword and similarity methods can run entirely in-house.

When methods disagree, insight emerges

Using these fictional profiles, the prototype produced independent scores and concise summaries of each candidate's strengths and weaknesses. The most interesting cases were not those where all scores aligned, but those where they diverged.

In one example, a candidate scored highly on semantic similarity and the LLM-based review, but poorly on keyword matching. Their background closely resembled that of strong hires, and the model identified clear potential - yet the absence of specific terms kept the keyword score low.

This kind of divergence flags candidates who merit closer attention rather than automated rejection. It is precisely where human judgment becomes essential.

From prototype to practice at Argusa

Building the prototype highlighted that when candidates can polish applications using AI, better scoring methods alone are not enough.

The question becomes: how do we design questions that create authentic signal?

Argusa’s applicant tracking system (Jotform, Zapier, Jira) is intentionally modular, allowing rapid iteration on question design. Our current work focuses on using this flexibility to implement a different approach: a system of questions designed to preserve meaningful signal even when candidates use AI. These questions emphasize prioritization, reflection, and grounding in experience rather than fluent description alone.

For example, candidates are asked to rank five realities of consulting work - parallel projects, client travel, diverse technical contexts, tight deadlines, and stakeholder communication - from “most excited” to “most concerned,” then briefly explain both extremes. Other questions ask candidates about a concrete experience, such as describing a particularly challenging project - what made it difficult, how they approached it, and what they learned.

The unifying design principle is constraint. Forced-choice questions surface priorities and trade-offs, while experience-based questions anchor responses in concrete situations. AI can assist with expression, but constrained questions shift responsibility for substance back to the candidate.

The future we choose

Building these systems has reinforced one lesson: the question is not whether to use automation in hiring, but how to design it.

When candidates use AI to generate applications and companies rely on automated screening, hiring systems can no longer be designed as they were in the past. The location of meaningful signal has shifted, and systems must adapt accordingly.

Yet one dimension of hiring remains fundamentally resistant to automation: whether you can imagine working with someone. This judgment reflects how a person communicates, responds to uncertainty, and engages with others - information that only emerges through interaction.

The real risk is not that automation makes decisions faster than humans. It is that poorly designed automation makes decisions quietly without prompting anyone to look again at the candidate who does not fit the template.

Automation in hiring is inevitable. Whether it helps organizations discover talent or systematically overlook it depends on how intentionally these systems are designed.

Author

Michaela Mlynáriková

Candidates use AI. Companies rely on automated screening. The result: signal dilution and missed talent. How to design hiring systems that still work when AI is everywhere.

It started the same way every time.

"We have decided not to proceed with your application".

I have a PhD in particle physics and spent over a decade at CERN, including several years of leading international research teams. I could not get past the first round of automated job screening.

The rejection emails were polite and identical. Several colleagues with impressive backgrounds ran into the same invisible barrier. That raised a question: What exactly happens at the first stage of hiring today and what kind of signal does it actually detect?

The current state of automated screening

Most large organizations rely on automated systems to manage the initial round of applications. These systems scan résumés for job titles, skills, and certifications, ranking candidates based on keyword matches.

The efficiency is undeniable, but so are the limitations.

A "Software Engineer" may pass while a "DevOps Engineer" is rejected, even when the skills overlap. Leadership experience can disappear if it is phrased differently from the expected template. Two people can describe the same role in different ways, but software rarely sees beyond the wording.

Somewhere in those systems, a decade of analytical work was reduced to a mismatch between "particle physics" and "data consulting". Different words. Case closed.

When I eventually joined Argusa, I asked my manager what made my application stand out.

She smiled and said, "I review all the applications manually".

That single sentence changed my perspective.

Manual review works in small companies. But once hundreds of applications arrive every week, it becomes unrealistic. The question is no longer whether to automate, but how to do so without losing signal.

The other side: candidates adapt

Another force reshaping hiring today sits on the candidate side.

AI tools help candidates draft CVs, tailor cover letters, and answer application questions - often across many applications. In practice, applicants apply broadly because that is what the current market demands.

Recruiters increasingly encounter near-identical phrasing, generic motivation statements, and occasional copy-paste artifacts like "Would you like me to continue?".

The result is signal dilution.

When everyone can produce polished, competent-sounding text instantly, traditional signals such as motivation, communication skill, even attention to detail lose their differentiating power. The challenge is no longer filtering for quality writing, but for authentic signal beneath the polish.

Hiring systems were designed for a world where polish correlated with effort and intent. That world no longer exists.

A prototype: combining perspectives instead of choosing one

As part of recent work on internal systems at Argusa, I built a small proof of concept to explore an alternative design principle: instead of collapsing candidates into a single score, could multiple interpretable perspectives surface profiles that single-method screening often overlooks?

This prototype was exploratory and was never used in real hiring. It compared fictional candidate CVs to profiles of strong hires using three complementary approaches:

- Semantic similarity: Measures how closely each CV resembles those of our best hires in structure, focus, and language.

- Keyword match: A traditional checklist against required skills.

- AI evaluation (LLM-based review): A written assessment summarizing how a candidate’s background aligns with the role.

Showing multiple scores mirrors how hiring works in practice: we involve multiple interviewers precisely because no single perspective captures the full picture.

However, this approach also has an important limitation: comparing candidates to past “strong hires” can reinforce existing bias if used blindly. This is why these perspectives are intended to inform human review rather than replace it.

Note on data and confidentiality: All CVs used by this prototype were fictional and AI-generated; no real Argusa candidate data was used.

The prototype was designed with anonymization built in, so that even with real candidate data, LLM-based evaluation would operate only on redacted, non-identifying information, while keyword and similarity methods can run entirely in-house.

When methods disagree, insight emerges

Using these fictional profiles, the prototype produced independent scores and concise summaries of each candidate's strengths and weaknesses. The most interesting cases were not those where all scores aligned, but those where they diverged.

In one example, a candidate scored highly on semantic similarity and the LLM-based review, but poorly on keyword matching. Their background closely resembled that of strong hires, and the model identified clear potential - yet the absence of specific terms kept the keyword score low.

This kind of divergence flags candidates who merit closer attention rather than automated rejection. It is precisely where human judgment becomes essential.

From prototype to practice at Argusa

Building the prototype highlighted that when candidates can polish applications using AI, better scoring methods alone are not enough.

The question becomes: how do we design questions that create authentic signal?

Argusa’s applicant tracking system (Jotform, Zapier, Jira) is intentionally modular, allowing rapid iteration on question design. Our current work focuses on using this flexibility to implement a different approach: a system of questions designed to preserve meaningful signal even when candidates use AI. These questions emphasize prioritization, reflection, and grounding in experience rather than fluent description alone.

For example, candidates are asked to rank five realities of consulting work - parallel projects, client travel, diverse technical contexts, tight deadlines, and stakeholder communication - from “most excited” to “most concerned,” then briefly explain both extremes. Other questions ask candidates about a concrete experience, such as describing a particularly challenging project - what made it difficult, how they approached it, and what they learned.

The unifying design principle is constraint. Forced-choice questions surface priorities and trade-offs, while experience-based questions anchor responses in concrete situations. AI can assist with expression, but constrained questions shift responsibility for substance back to the candidate.

The future we choose

Building these systems has reinforced one lesson: the question is not whether to use automation in hiring, but how to design it.

When candidates use AI to generate applications and companies rely on automated screening, hiring systems can no longer be designed as they were in the past. The location of meaningful signal has shifted, and systems must adapt accordingly.

Yet one dimension of hiring remains fundamentally resistant to automation: whether you can imagine working with someone. This judgment reflects how a person communicates, responds to uncertainty, and engages with others - information that only emerges through interaction.

The real risk is not that automation makes decisions faster than humans. It is that poorly designed automation makes decisions quietly without prompting anyone to look again at the candidate who does not fit the template.

Automation in hiring is inevitable. Whether it helps organizations discover talent or systematically overlook it depends on how intentionally these systems are designed.

Author

Michaela Mlynáriková